R.K. Laxman, hailed as India’s first cartoon-maker, created The Common Man, drew over 30,000 cartoons, won the Ramon Magsaysay Award, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Vibhushan, and made satire an inseparable part of India’s democratic journey.

The Cartoonist Who Defined Indian Satire

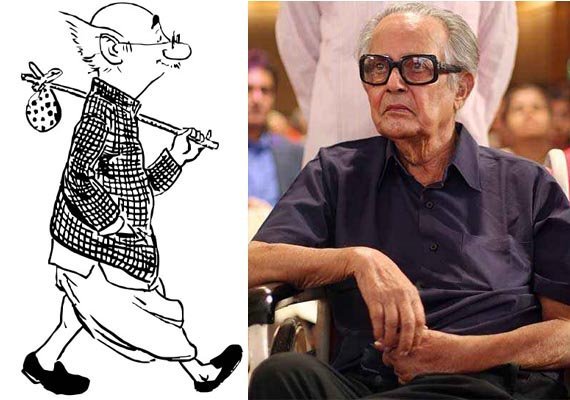

Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Laxman, popularly known as R.K. Laxman, is remembered as India’s most iconic cartoonist — the man who transformed cartoon-making into a daily ritual for millions. His creation, The Common Man, with his trademark dhoti, checked coat, and silent bewilderment, became the face of India’s middle class. His pocket cartoon series “You Said It” in The Times of India ran for over five decades, making him the first cartoonist in India to achieve such consistency and mass appeal. Starting at The Free Press Journal in Mumbai, Laxman rose to become a chronicler of Indian democracy, admired by citizens and leaders alike.

Early Life, Influences, and First Steps in Art

Born on 24 October 1921 in Mysore, Laxman was the youngest of six siblings in a Tamil-speaking family. His elder brother was the celebrated writer R.K. Narayan, and Laxman would go on to illustrate Narayan’s novels, including Malgudi Days. Even as a child, he was known for filling his notebooks with sketches of crows, dogs, and everyday street scenes. His lifelong fascination with crows became evident in the way they often appeared in his cartoons as side characters.

He was deeply inspired by the works of Sir David Low, the British political cartoonist, whose sharp critiques of authoritarianism during World War II shaped Laxman’s understanding of satire as a tool for democracy.

When he applied to the prestigious Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, he was rejected with the remark that his work lacked quality. Instead, he completed a degree in Politics, Economics, and Philosophy from the University of Mysore. During this period, he published illustrations in local newspapers and the Kannada humour magazine Koravanji, laying the foundation for his career.

From Free Press Journal to Times of India

In 1946, Laxman moved to Mumbai and joined The Free Press Journal, where he worked alongside Bal Thackeray (who would later found the Shiv Sena). Their careers diverged, but both sharpened their political commentary at the same desk.

Laxman’s big break came in 1951, when he joined The Times of India. That same year, he introduced his pocket cartoon column “You Said It.” It quickly became a daily staple for readers across India. For over 50 years, readers admitted they often checked his cartoon before reading the headlines. This unique status made him not just a cartoonist but an essential part of India’s newspaper culture.

By the time he retired, he had drawn over 30,000 cartoons, creating one of the most extensive cartoon archives in the world.

The Common Man: A National Symbol

In 1957, Laxman introduced The Common Man, who would become his most enduring creation. This dhoti-clad, bespectacled figure never spoke, because, as Laxman explained, “in our country, the common man has no voice.” The Common Man represented the middle-class Indian — patient, frustrated, and quietly resilient.

Through “You Said It,” the Common Man witnessed every turning point in India’s history:

- Nehru’s socialism, often depicted as lofty but impractical.

- Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975–77), where silence in cartoons reflected censorship.

- Rajiv Gandhi’s modernisation left ordinary citizens confused.

- 1991 liberalisation reforms, when the Common Man looked lost amidst economic jargon.

- Coalition governments of the 1990s, mocked for instability and constant compromises.

The Common Man achieved cultural immortality. He was honoured on Indian postage stamps (1988), became the mascot for Air Deccan, and was commemorated with statues in Pune and at Symbiosis Institute. For ordinary readers, he was more than a cartoon character; he was a mirror.

Cartoons as Political Criticism

R.K. Laxman used cartoon-making to criticise politics and political leaders while maintaining wit and balance. Unlike fiery critics, he avoided personal attacks and focused on exposing systems and absurdities.

His cartoons highlighted:

- Corruption and scams, showing leaders promising change while citizens remained helpless.

- Inefficient bureaucracy, depicted as endless queues and paperwork.

- Inflation and price rise, where the Common Man always suffered silently.

- Authoritarian tendencies, especially during the Emergency, when his muted satire became symbolic resistance.

Even though leaders were often targets, they respected him. Jawaharlal Nehru, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Manmohan Singh openly admired his work, and some framed his cartoons in their offices. His success lay in the fact that both politicians and citizens laughed at the same sketch, even when the joke was on them.

Achievements, Awards, and Global Recognition

Laxman’s work earned him both national and international acclaim:

- Padma Bhushan (1973)

- Ramon Magsaysay Award (1984) for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication

- Padma Vibhushan (2005)

- Google Doodle tribute (2015) on his 94th birthday

- Exhibitions in London, Tokyo, and New York

He also ventured beyond cartoons. His autobiography “The Tunnel of Time”, his anthology The Distorted Mirror, and his novel The Hotel Riviera showcased his versatility. He collaborated with his wife, Kamala Laxman, on children’s books (The Thama Series) and created the iconic Asian Paints mascot “Gattu” in 1954.

Struggles, Controversies, and Public Perception

R.K. Laxman’s career was not without struggles. His early rejection at art school nearly derailed him, and in later life, he battled diabetes and multiple strokes (2003 and 2010). Despite paralysis, he retrained his left hand to continue cartooning.

Controversy came from critics who argued he avoided deeper issues such as caste and gender inequality. Some accused him of portraying the Common Man as too passive, normalising helplessness. Yet society overwhelmingly embraced him. For most readers, his subtle satire captured exactly what they felt but could not say. His cartoons were clipped, preserved, and even sent in letters to him by loyal readers.

He was unique in being accepted across political lines. Both Left and Right-wing leaders accepted his satire because he spared none. This non-partisanship is why society remembers him not just as a cartoonist, but as India’s conscience in ink.

His Legacy After Death

R.K. Laxman passed away on 26 January 2015 — Republic Day. The symbolism was striking: the man who chronicled democracy left on the day democracy itself is celebrated. Parliament observed silence in his honour, newspapers carried tribute cartoons, and artists across the country drew the Common Man in mourning.

After his death, his legacy was institutionalised:

- The Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Pune, set up a permanent exhibition of his works.

- In 2022, the R.K. Laxman Museum was inaugurated in Pune, showcasing his original sketches, archives, and personal memorabilia.

- His cartoons continue to be taught in journalism and political science courses, ensuring his influence on new generations.

A Pencil That Outlived Power

R.K. Laxman was more than a cartoonist. He was India’s first true cartoon-maker, a man who turned satire into a national habit and humour into a political mirror. Through The Common Man, he gave dignity to silence, humour to frustration, and visibility to ordinary citizens. His pencil outlasted governments, captured history, and shaped the way India understood politics.

Even today, in an era of memes and instant outrage, Laxman’s cartoons remain relevant for their balance, restraint, and timeless humour. His Common Man still stands in the corner of Indian democracy — silent, watchful, and unforgettable.

FOR MORE BLOGS – beyondthepunchlines.com

Add to favorites

Add to favorites